The worst of the fighting took place in the town of Nochixtlan Oaxaca.

In that town, various human rights groups are calling out the Mexican government after eyewitness accounts and various photographs point to Mexican cops firing at the rioting teachers, Mexico’s SinEmbargo.MX reported.

The ongoing hostilities have resulted in a wave of

criticism at the Mexican government. Mexico’s Human Rights Commission

(CNDH) issued a warning asking the government for cooperation. The group

claims to have sent their researchers out to look into various claims

of human rights violations. Multiple other organizations have issued

their condemnation at the events in Oaxaca.

SOME OF THE DEAD TEACHERS, AS REPORTED AT THE WEBSITE LINKED ABOVE.

Photo courtesy of Regeneración Radio.

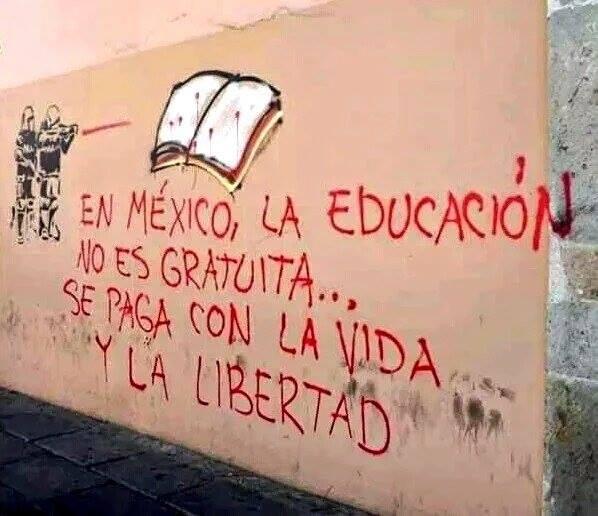

TRANSLATION:

TRANSLATION:

"In Mexico education is not free. It is paid for with life and with freedom.”

"Employees may travel to the tourist destinations of Puerto Escondido and Huatulco but only if they go by air."

BECAUSE THIS IS HAPPENING IN MEXICO, AGAIN, FEW SEEM CONCERNED ENOUGH TO GIVE US THE TRUTH ON THIS DECADE'S-OLD STRUGGLE, BUT THE TEA ROOM HAS FOUND LOCAL SOURCES THAT WILL EXPLAIN WHAT'S REALLY HAPPENING UNLIKE THE SLATE ARTICLE BELOW WHICH I INCLUDE HERE JUST TO SHOW YOU HOW THIS HAS BEEN "SPUN" BY OUR MEDIA...

FROM AN ARTICLE BY SLATE MAGAZINE, WHICH OBVIOUSLY HAS NO CLUE WHAT'S REALLY BEHIND THIS VIOLENCE.

"A strike by the country’s largest teachers union has turned into a violent confrontation with police.

At last (disputed) count, nine people, including one journalist , have been killed, about 100 (a combination of civilians and police officers) have been injured, and at least 20 arrested. It’s a tragic culmination of what should’ve been a peaceful dispute over what the future of education in Mexico should look like.First, some glancing background, since this was by no means an out-of-thin-air showdown:

For decades, the left-leaning Oaxaca teachers union, the National Coordinator of Education Workers (or CNTE), has gone on annual strikes that usually yielded modest pay raises. In 2006, the state governor sent in 750 police officers to break up the strikes, upping the ante considerably. In the end, the ceremonial strikes became a full-scale civic rebellion that lasted more than six months and led to more than a dozen deaths.

More than a million kids were out of school for the duration.

Over the past several years, the strikes of Sección 22, as the Oaxaca chapter of CNTE is known, have had a different focus: the education reforms pushed by President Enrique Peña Nieto, passed the year after he entered office in 2013.

The reforms, an attempt to modernize Mexico’s flailing education system and therefore the country as a whole, mandate a test given to teachers as well as a performance review. If teachers fail three times in a row, they could be fired, stripped of the job security they’ve traditionally enjoyed. It's an evaluation system that's completely without precedent in the history of Mexican education.

In the run-up to this weekend’s conflagration, the government has fired teachers en masse for striking and jailed several Sección 22 leaders on money laundering

charges. The union, meanwhile, no stranger to violent tactics, has shut

down streets, disrupted traffic on the highway between Mexico City and

Oaxaca, and blocked access to an important oil refinery in the region.

Then, on Sunday, the explosion. Protesters in Oaxaca threw rocks and

Molotov cocktails and set cars on fire; riot police took over and “unknown gunmen” opened fire on the crowd in an apocalyptic scene that one El País correspondent aptly compared to Iraq.

While the Associated Press filmed at least one policeman shooting a gun, the government denies that the federal police were armed; there were also state police present..

Chaos reigned."

THE GOVERNMENT LIED!

THE MASSACRE OF 2006 WAS CARRIED OUT BY ARMED POLICE!

THE SHOOTINGS THIS WEEK OF RESIDENTS WERE CERTAINLY CARRIED OUT BY THOSE ARMED "POLICE" WHO HAVE A DOCUMENTED TENDENCY TO LOATHE AND ASSAULT AND MURDER INDIGENOUS PEOPLE.

THAT THE CURRENT MEXICAN REGIME ORDERED IN RIOT POLICE SOONER THAN IN 2006 SIMPLY ADDED FUEL TO THIS FIRE.

TO SEE WHAT LOCALS ARE UP AGAINST, FOR ANY WHO HAVE NEVER VISITED MEXICO AND EXPERIENCED FIRST-HAND HOW CORRUPT THE LOCAL POLICE CAN BE, READ THE FOLLOWING ESSAY.

IT IS A SCATHING ARTICLE FROM FIRST-HAND OBSERVATION AND RESEARCH, FROM INTERVIEWS WITH THOSE WHO HAVE EXPERIENCED POLICE BRUTALITY ON AN ORDER WE DON'T EVEN SEE IN AMERICA.

"Alongside this rise in crime—and with accelerating intensity since the violent events of September 11, 2001—punitive policing agendas and hard-line security practices have come to define the role of local government in cities across the Americas. Punitive policing has set the tone for social control.

Governments have suspended limits on the coercive powers of police, the actions of parastatal vigilantes and the authority of state security forces.

Torture, militarized policing, lethal force, detention without trial and denial of citizenship to criminalized immigrant populations have increasingly been deemed necessary, or have become mainstream policy options even in long established democracies.

Politicians and government officials use fear of crime to win elections, increase government expenditures and discredit political opposition.

Such campaigns are most successful when they play on public fears of particular target populations.

A symbiotic relationship then develops between politicians and the media and becomes a catalyst for contrived crises.

The media echoes the discourse of politicians during election campaigns, while increased media coverage of an issue increases pressures on politicians to provide solutions. Increased coverage and sensationalization of crime, along with a linkage implied or portrayed between crime and race or ethnicity, intensify the boundaries drawn between majority and minority communities. "

THAT SOUNDS VERY FAMILIAR, DOESN'T IT?

Let's do as my grandfather always advised and go to the people themselves, those who are there and have been there all these years.

FROM The North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA), an independent, nonprofit organization founded in 1966 that works toward a world in which the nations and peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean are free from oppression and injustice.

LIFE AFTER THE MASSACRE

“I thought that it was raining,” education students wrote the day after police killed as many as 12 and injured dozens at protests in the majority- indigenous southern Mexican state of Oaxaca on June 19. “But Oaxaca is crying.”

The heavy evening rain that followed the massacre accentuated the atmosphere of mourning and resignation – but also rage and resilience – the following day. Rarely have I seen so many stores closed in Oaxaca City, even in 2006, when a similar pattern of protest and repression led to the six-month popular takeover of Oaxaca City to protest the state government’s repression of striking education workers.

Some residents feared a federal police assault on the central city plaza (Zócalo), where education workers and supporters continued to hold an occupation (plantón).

The movement’s main demand: the end of the neoliberal “education reform” enacted in 2012, which eliminated the constitutional guarantee of a free public education established in Mexico after the Mexican revolution 100 years ago.

Other residents took the day to march in protest against the federal police’s armed intervention.

The blunt rhythm of their chant— “Assassins! Assassins! Assassins!”— ricocheted off the stone buildings of the central plaza, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Though education workers and supporters staged a large mega-march a week earlier, before the killings, this march sent an even stronger message to the state and federal governments.

Protesters continued to stream into the plaza more than two hours after the first ones had arrived. Some education workers I spoke with had left the rural district of Putla at 3 A.M. to arrive in Oaxaca City in time for the protest. Others had slept overnight in the Zocálo.

In indigenous towns elsewhere in the state, families held public funerals for the slain.

[NOTE: BELOW I WILL OUTLINE THE INDIGENOUS MAKEUP OF THIS AREA SO ONE CAN SEE WHY OAXACA MAY BE TARGETED MORE OFTEN AND MORE RADICALLY THAT OTHER AREAS IN MEXICO WHICH ALSO HAVE SIMILAR PROTESTS THAT ALMOST NEVER MAKE THE NEWS HERE IN AMERICA.]

In 2016, the support looks different, yet recent events make evident its breadth. Oaxaca City is no longer the main site of contention.

While Sección 22 has called for strategic road blockades in Oaxaca, the union’s state assembly itself never actually called for the takeover of the main highway to Mexico City at Nochixtlán, as Luis Hernández Navarro has noted.

Parents and supporters in this highly indigenous (Ñuu Savi) town helped lead the way, and they are now demanding explanations for why the federal police chose to attempt an eviction on the town’s market day, when thousands of regional residents visit the town to buy and sell.

As the police attacked on June 19, officers peppered their tear gas volleys with racial slurs.

In nearby Chiapas, another majority-indigenous state, education workers have also stood up to the reform, and teachers reported that police called them “damn monkey-eaters.”

Since the killings, Mexican supporters have staged marches everywhere from Cancún to conservative Chichuahua and Monterrey, and numerous cities across the globe have been witness to local actions.

The United Nations is investigating the attack in Nochixtlan for excessive use of state force and in denying medical care to civilian victims, an international war crime. Many in the area report that the main hospital attended only wounded police. One Oaxaca City doctor told me doctors who came to help were retained at regional police checkpoints.

The repressive strategies of the state and federal government resemble those in 2006, but also differ in significant ways.

In 2006, residents prevented the police from controlling the city for six months until the federal police arrived.

In 2016, state and federal governments sent in the federal police after only one month.

As Scott Campbell has noted, no single day in 2006 was as fatal as June 19, 2016.

In the evening after the murders, as movement supporters built barricades around the Zocálo in light of what seemed to be an eminent attack, federal police helicopters swept slow and low over downtown streets, intimidating locals with the thunder of their engines.

Earlier that day, helicopters had veered, extra-low, into the sea of protesters, repelling them with the sheer force of the air currents produced by rotor blades, much like the water cannons used against them in 2006. In blockades in the Isthmus region, education workers reported spy drones circling their encampment.

Yet other control strategies, like the terror inspired by selective killings, closely resemble those of 2006.

On Sunday, a community journalist and anarchist was killed in Huajapan (near Nochixtlán), where he long supported the radio station Tu un Ñuu Savi (Voice of the People of the Rain), which played a critical role in spreading information on the 19th.

In Oaxaca City, armed porros (hired thugs) roamed Radio Universidad in the nights after the 19th, and movement supporters guarding the radio de-escalated confrontations.

As in 2006, the state government has successfully blocked the frequency of Radio Plantón, the union’s radio station, leaving Radio Universidad as the sole radio voice of the movement in the capital city.

In Nochixtlán, the mayor-elect has affirmed that locals live in a kind of psychosis.

Many injured by firearms are scared to seek medical help for fear of being captured by police. Likewise, in 2006, some teachers buried documents that identified them as teachers for fear of being persecuted.

The local media has also contributed to the fear by inspiring public anxiety about the movement itself. The PRI-supporting El Imparcial has followed the governor’s lead in distinguishing “good” protesters from “bad” ones as a divide-and-control strategy.

According to the media, the downtown barricades the night of the 19th were populated by “common criminals” and people dedicated to “assault,” the newspaper claimed, and locals were terrified of being out at night.

Yet a friend and I spent several hours walking around the perimeter of the Zocálothat evening and into the early morning of June 20, at one point stopping for tacos at a taqueria open less than 100 feet from a barricade. I spent time at the downtown plantón after midnight several nights last week, and I have observed that a significant percentage of those occupying the plaza at night are women.

[NOTE: THE ASSOCIATED PRESS (AP) REPORTED THAT IT WAS NOT THE TEACHERS CAUSING THE LATEST VIOLENCE:

"Few teachers were involved in violence during a weekend protest in which 6 people died, Mexican police say; Federal Police Chief says Sunday's violence was perpetrated by other 'radical groups' - AP"

WHAT AP FAILED TO MENTION WAS THE UNMITIGATED POLICE BRUTALITY KNOWN TO EXIST THROUGHOUT MEXICO.]

“Urgent! Urgent! Evaluate the President!”

I spent much of June conducting interviews with working-class residents of Oaxaca City’s outer neighborhoods, and the slogan above — a chant often heard at education workers’ marches— nicely captures the double standards that outrage many of these residents feel.

Why do teachers face stringent standardized evaluation exams, but not politicians like the President, long ridiculed for being unable to list three books that have influenced him?

How can the government arrest and detain union leaders for corruption and other charges, when major political bosses – including Ulises Ruíz – commit mass fraud and violence, but are politically rewarded rather than punished?

Many Oaxacans have invested time and money in their local schools. Many helped to physically build them.

On weekends, through collective work arrangements called tequio, they help maintain and beautify schools.

They have done so even though the federal constitution guaranteed free public education.

While the June 19th killings reiterated for many Oaxacans the Mexican government’s willingness to write off their lives and labor, they also helped bring together a wide range of popular and indigenous struggles in the state, particularly around mining and energy projects.

Until double standards about government treatment of elites and everyday citizens, including union members, are addressed, life in Oaxaca after the June 19 massacre will likely continue to be defined by the wide-ranging movement against neoliberal education reform."

AS I SAID, THIS IS AN ONGOING CRISIS, BOILING FOR OVER A DECADE NOW, WITH SO MANY "DISAPPEARANCES" AND "UNSOLVED MURDERS" AS TO SEEM IMPOSSIBLE TO BELIEVE, BUT DEATH HAPPENS THERE, FREQUENTLY, AND SELDOM EXPLAINED AS LOCALS TELL IT.

November 27, 2015, MEXICO CITY (Reuters) -

"Eight men were found dead, their throats slit, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, a local emergency services official said.

"Eight men were found dead, their throats slit, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, a local emergency services official said.

The

bodies were discovered in a car in a municipality on the border with

the Gulf coast state of Veracruz, the official said in a message sent to

Reuters on Friday evening.

More than 100,000 people have been killed or gone missing in drug-related violence nationwide since 2006. "

More than 100,000 people have been killed or gone missing in drug-related violence nationwide since 2006. "

IS IT ALL "DRUG RELATED" OR IS THAT SIMPLY BEING USED TO MAKE PEOPLE "DISAPPEAR"?

WHAT BEGAN ONCE MORE AS PEACEFUL PROTESTS WERE ESCALATED BY POLICE PRESENCE AND THEIR ENSUING VIOLENCE AGAINST OAXACA CITIZENS.

"On June 19, the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca was the scene of a senseless massacre. The bloody battle took place in the rural town of Nochixtlan and resulted in the death of at least nine civilians. “Right now, the federal police are withdrawing, going back to their vehicles,” said a witness of the attack as he filmed the horrific scene.

Bullets are heard smashing against metal traffic barriers on the roadside as the camera image shakes. Taking heavy breaths he calmly continued, “And as they retreat, they are shooting at us with firearms.”

A week earlier, police crackdowns had begun in various regions of Oaxaca state.

These acts of violence are occurring in light of current protests in Oaxaca, where — since May 15— the teachers’ movement has set up a peaceful plantón, or encampment, in the city center, and dozens of roadblocks across the state, including Nochixtlan.Initially the federal police force denied they were carrying guns, however, as evidence mounted, they were forced to admit that they were in possession of weapons.

In addition to nine dead, the planned eviction on June 19 left over 100 people wounded and between 22 and 25 disappeared after a confrontation that lasted 15 hours — during which police used tear gas and automatic machine guns to repress the protesters.

Hospital workers on the scene were also attacked with tear gas."

THE POLICE THERE OFTEN POST GRAPHIC PHOTOS OF THE DEAD AND BOAST ABOUT THE KILLINGS.

THEIR HOPE SEEMS TO BE THAT SUCH POSTS WILL DISCOURAGE PROTESTS...

OR MAYBE THEY JUST LIKE TO GLOAT?

AND THAT IS REALLY HOW IT IS IN OAXACA.

JUST AS THE YOUNG AMERICAN GOVERNMENT BEGAN AN ETHNIC CLEANSING OF INDIGENOUS TRIBES AFTER THE SETTLERS OUTNUMBERED THE 'INDIANS', SO IT IS IN MEXICO, IN PERU, IN BRAZIL, IN ALMOST EVERY NATION TO OUR SOUTH, BUT ALSO ACROSS THE 'PONDS'.

LOOK AT THE ABORIGINES' STRUGGLE IN AUSTRALIA, THE OLD TRIBES OF AFRICA AND THE ETHNIC CLEANSING THERE.

WHEREVER THERE ARE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE WHO MAY STILL HAVE VALID CLAIM TO LANDS AND LAND RIGHTS, TO NATURAL RESOURCES, THERE IS ETHNIC CLEANSING.

THEY ARE SIMPLY BULLDOZED INTO AS NEAR OBLIVION AS ANY NATION CAN ACCOMPLISH WITHOUT ANY OTHER NATIONS SCREAMING OUTRAGE AT THEM FOR IT.

BUT EVEN WITH SCREAMS AGAINST GENOCIDES AND FREQUENT ETHNIC ASSAULTS, MOST NATIONS GO RIGHT ON DOING WHAT THEY HAVE BEEN DOING FOR CENTURIES....BURYING THE EVIDENCE THAT THOSE WHO ONCE OCCUPIED THE LAND HAD ANY RIGHT TO FIGHT AGAINST BEING ERADICATED.

FEW AMERICANS REALIZE THAT THE VAST MAJORITY OF WHAT WE CALL "MEXICANS" ARE ACTUALLY DESCENDED FROM INDIGENOUS TRIBES.

AS MANY AS 92% OF THE POPULATION OF MEXICO DO INDEED CARRY INDIGENOUS DNA, OFTEN IN SURPRISINGLY HIGH OR "PURE" QUANTITY.

THE NATIVE PEOPLE OF WHAT WE CALL 'MEXICO' SIMPLY DID NOT 'MIX' WITH THE CONQUERORS QUITE AS MUCH AS OUR MORE NORTHERN TRIBES HAVE OVER THE CENTURIES.

THE VAST MAJORITY OF 'MEXICANS' TODAY HAD ANCESTORS WHO WATCHED THE FIRST BOATLOADS OF INVADERS ARRIVE...THEY WERE THE RIGHTFUL INHABITANTS OF THAT AREA OF THE CONTINENT, AND THEIR HUNTING GROUNDS AND MIGRATORY PATTERNS RANGED ALL THE WAY UP TO AMERICA'S CURRENT OREGON STATE BORDER AND ALL THE WAY TO THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER.

CALIFORNIA WAS OVERWHELMINGLY "MEXICAN" TERRITORY, AS WERE THE 'BORDER STATES' ALONG THE RIO GRANDE.

THE ONLY 'BORDER CROSSING GUARDS' BEFORE THE INVASIONS WERE THE LOCAL TRIBES IN NORTH AMERICA WHO MAY HAVE CONTESTED WITH THE TRIBES FROM THE SOUTH FOR HUNTING GROUNDS AND SETTLEMENTS.

TODAY, IN MEXICO AS ELSEWHERE, THE "STATE" IS STILL AFRAID OF "INDIAN UPRISINGS" AND SO ATTENDS TO THAT FEAR WITH JUST SUCH AS WE ARE SEEING AGAIN IN OAXACA.

Cultural genocide and resistance

With as many as 16 local indigenous languages, Oaxaca represents one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse states in Mexico.

Furthermore, Oaxaca is rich in natural resources, with a long history of indigenous and campesino resistance, as well as one of the highest poverty rates in the country.

While corrupt government officials and transnational investment companies have denied people of their rights and appropriate their land under the pretence of “progress,” rural and indigenous communities often suffer consequences such as eviction, extortion, cultural annihilation and other forms of abuse and theft.

According to the CNTE (National Coordinator of Education Workers Union) , the recent reforms are nothing more than a continued attempt to promote homogeneity and an unceasing legacy of racist oppression in an already markedly unequal nation.

Oaxaca, and in particular the teachers of Section 22 of the CNTE, have played an important role in resisting the reforms, garnering the support from dissident groups all over Mexico; day laborers of San Quintin, the Mexican Electricians Union, health workers, university students, parents of the 43 missing Ayotzinapa students and the Zapatistas National Liberation Army in Chiapas are only a few examples of the teachers’ national advocates.

They support the movement against the privatization of education, as well as the right to access public services, labor rights, food sovereignty and an end to violence in the country.

Misleading public opinion

The teachers’ dissidence has not been beneficial to the Mexican state, challenging its power over the population. Scapegoating the teachers as the root of the problem in the media has been the easiest way for the government to take attention away from failures of the system, seriously underfunded public services and corporate greed and abuse."

IF YOU ARE OF THIS LINEAGE AND ARE TRYING TO CONNECT TO YOUR ANCESTRY, PLEASE SEE THE INFORMATION NEAR THE BOTTOM OF THIS POST.

THE REST THAT FOLLOWS IS HISTORY, FACTS ABOUT THE REGION, SO THOSE WHO DON'T CARE TO KNOW SUCH MAY END HERE.

HISTORY OF OXACA

The Zapoteca who ruled over the oxaca region before the Spanish invasion were skilled in astronomy and excavation, and leveled the top of a local mountain around 450 B.C.to create the ceremonial center now called Monte Albán.

One of the most densely populated ancient cities in Mesoamerica, Monte Albán is estimated to have had 18,000 Zapotecan residents at its peak.

San José Mogote, considered the oldest agricultural city in the Oaxaca Valley, was probably the first area settlement to use pottery.

Historians also credit Zapotecas with constructing Mexico’s oldest-known defensive barrier and ceremonial buildings around 1300 B.C. The culture also predates any other in the state in the use of adobe (850 B.C.), hieroglyphics (600 B.C.) and architectural terracing and irrigation (500 B.C.).

By the 15th century BCE, the Aztecs had arrived in Oaxaca and quickly conquered the local inhabitants, establishing an outpost on the Cerro del Fortín.

Consequently, trade with Tenochtitlán and other cities to the north increased, but the basic fabric of living was unchanged by the Aztec presence.

Oaxaca’s coat of arms, above, features a red background that commemorates the many battles that have been fought in the state. The top of the design is adorned with an eagle holding a snake atop a cactus, Mexico’s national symbol. Seven silver stars represent the state’s seven geographical regions: Istmo (isthmus), Costa (coast), Papaloapan (river basin), Sierra (mountains), Mixteca (Mixtec territory), Valles Centrales (central valleys) and Cañada (woodlands).

The emblem’s central oval is bordered by the phrase “Respect for the rights of others will bring peace.” At the bottom of the oval, two hands are breaking a chain, symbolizing Oaxaca’s struggle against colonial domination.

On the left is an indigenous symbol for Huaxycac, the first Oaxacan region settled by the Spanish conquistadors. To the right are the Mitla Palace and a Dominican cross, representing Oaxaca’s indigenous history and its ties to Catholicism.

THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLE OF CENTRAL MEXICO.

When Hernán Cortés and his expedition reached the eastern shore of México in 1519, it is believed that at least 180 separate languages were spoken within the boundaries of the present-day republic. And thanks to the isolation and cultural divergence that has taken place in southern México since the Conquest the Republic is now home to some sixty ethnic groups speaking almost 280 separate languages.

Today, the genetic, cultural, and spiritual remains of the first inhabitants of México remain strong within the spirit of the Mexican people. An understanding of this history and the evolution of these people is a key to understanding the pride that Mexican people feel towards their ancestors.

The Federal District. The Distrito Federal is located in the south central portion of México. It shares borders with the states of México (on the west, east and north) and Morelos (on the south). The District occupies 1,547 square kilometers, which is equal to 0.1% of the national territory. In contrast, the population of Distrito Federal was 8,605,239 in 2000, equal to 8.83% of the national population. Politically, the District has no municipios, but is divided into sixteen political districts (delegaciones políticas).

Estado Libre y Soberano de México. The Free and Sovereign State of México is located in the center-south section of the Mexican Republic. This landlocked state has common boundaries with Querétaro de Arteaga and Hidalgo on the north, Puebla and Tlaxcala on the east, Distrito Federal, Guerrero and Morelos on the south and Michoacán de Ocampo on the west. The capital of México is Toluca, which had a population of 1,080,081 in 1995, making it the sixth largest city in the entire Republic of México.

The state of México - with a population of 13,096,686 in the 2000 census - contains 13.43% of the total population of the Mexican Republic. However, the state has an area of 21,196 square kilometers, which represents only 1.1% of the national territory. Politically, the state of México is divided into 121 municipios.

Historical Notes on the Indigenous People of the Valley of México

Today - as in the past - México City, the Federal District, and the State of México represent both the economic, cultural and political center of the Mexican Republic. México City itself is located on a large dry lakebed in a highland basin at an elevation of about 7,400 feet. The basin is surrounded by towering mountain ranges, including the Popocatépetl and Ixtaccíhuatl volcanoes.

Over the millennia the Valley of México's inhabitants have included the ancient Aztec (Mexica), Toltec and Chichimeca tribes, cultures which left a wealth of relics and ruins in the area that have attracted and amazed tourists and visitors throughout it's history. The City of México is built on the ruins of Tenochtitlán, which was the capital of the Aztec Empire.

The story of the Aztec Empire is a rags to riches story, which has fascinated historians and students alike for many centuries. The Mexica (pronounced "me-shee-ka") Indians, the dominant ethnic group ruling over the Aztec Empire from their capital city at Tenochtitlán in the Valley of México, had very obscure and humble roots that made their rise to power even more remarkable. The Valley of México, which became the heartland of the Aztec civilization, is a large internally drained basin, which is surrounded by volcanic mountains, some of which reach more than 3,000 meters in elevation.

The growth of the Mexica Indians from newcomers and outcasts in the Valley of México to the guardians of an extensive empire is the stuff that legends are made of. Many people, however, are confused by the wide array of terms designating the various indigenous groups that lived in the Valley of México. The popular term, Aztec, has been used as an all-inclusive term to describe both the people and the empire.

The noted anthropologist, Professor Michael E. Smith of the University of New York, uses the term Aztec Empire to describe "the empire of the Triple Alliance, in which Tenochtitlán played the dominant role." Quoting the author Charles Gibson, Professor Smith observes that the Aztecs "were the inhabitants of the Valley of México at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Most of these were Náhuatl speakers belonging to diverse polities and ethnic groups (e.g., Mexica of Tenochtitlán, Acolhua of Texcoco, Chalca of Chalco)." In short, the reader should recognize that the Aztec Indians were not one ethnic group, but a collection of many ethnicities, all sharing a common cultural and historical background.

On the other hand, the Mexica, according to Professor Smith, are "the inhabitants of the cities of Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco who occupied adjacent islands and claimed the same heritage." And it is the Mexica who eventually became the dominant people within the Aztec Empire. Legend states that the Mexica Indians originally came to the Valley of México from a region in the northwest, popularly known as Atzlan-Chicomoztoc. The name Aztec, in fact, is believed to have been derived from this ancestral homeland, Aztlan (The Place of Herons).

In A.D. 1111, the Mexica left their native Aztlan to settle in Chicomoztoc (Seven Caves). According to legend, they had offended their patron god Huitzilopochtli by cutting down a forbidden tree. As a result, the Mexica were condemned to leave Aztlan and forced to wander until they received a sign from their gods, directing them to settle down permanently.

The land of Atzlan was said to have been a marshy island situated in the middle of a lake. Some historians actually consider the names "Chicomoztoc" and "Aztlan" to be two terms for the same place, and believe that the island and the seven caves are simply two features of the same region. For nearly five centuries, popular imagination has speculated about the location of the legendary Aztlan. Some people refer to Aztlan as a concept, not an actual place that ever existed.

However, many historians believe that Aztlan did exist.

The historian Paul Kirchhoff suggested that Aztlan lay along a tributary of the Lerna River, to the west of the Valley of México. Other experts have suggested the Aztlan might be the island of Janitzio in the center of Lake Pátzcuaro, also to the west, with its physical correspondence to the description of Aztlan.

Many people have speculated that the ancestral home of the Aztecs lay in California, New Mexico or in the Mexican states of Sonora and Sinaloa. All of the latter-named locations are home to indigenous groups who belong to the Uto-Aztecan linguistic groups.

The northern Uto-Aztecans occupied a large section of the American Southwest. Among them were the Hopi and Zuni Indians of New Mexico and the Gabrielino Indians of the Los Angeles Basin.

Also included in this linguistic group are the Paiute (of California, Oregon, Nevada, and Idaho) and the Ute (of Wyoming, Colorado, and Utah). The Central Uto-Aztecans - occupying large parts of Chihuahua, Sinaloa and Sonora in northwestern México - included the Papago, Opata, Yaqui, Mayo, Concho, Huichol and Tepehuán. Most historians agree that where there is a linguistic relationship, there is most likely also a genetic relationship.

It is, therefore, logical to assume that the Mexica would share common roots with other Uto-Aztecan groups, and that the legendary Aztlan was located in northwestern México or the Southwestern United States.

"The north-to-south movement of the Aztlan groups is supported by research in historical linguistics," writes Professor Smith in The Aztecs, "The Náhuatl language, classified in the Nahuan group of the Uto-Aztecan family of languages, is unrelated to most Mesoamerican native languages." As a matter of fact, "Náhuatl was a relatively recent intrusion" into central México.

It is important to note, however, that the Aztlan migrations were not one simple movement of a single group of people. Instead, as Professor Smith has noted, "when all of the native histories are compared, no fewer than seventeen ethnic groups are listed among the original tribes migrating from Aztlan and Chicomoztoc."

It is believed that the migrations southward probably took place over several generations.

"Led by priests," continues Professor Smith, "the migrants stopped periodically to build houses and temples, to gather and cultivate food, and to carry out rituals."

The first group of migrants probably included the Acolhua, Tepaneca, Culhua, Chalca, and Xochimilca, all of who settled in the Valley of México.

The second group, including the Tlahuica of Morelos, the Matlatzinca of Toluca Valley, the Tlaxcalans of Tlaxcala, the Huexotzinca of Puebla, and the Malinalca of Malinalco, migrated to the surrounding valleys.

The last to arrive, around A.D. 1248, were the Mexica who found all the good land occupied and were forced to settle in more undesirable locations of the Valley.

When the Mexicas first arrived in the Valley of México, the whole region was occupied by some forty city-states (altepetl is the Nahua term). These city-states - which included the Tepanecs, Coatlinchans, Cholcos, Xochimilcos, Cholulas, Tlaxcalans and Huexotzincas - were engaged in a constant and continuing battle for ascendancy in the Valley. In describing this political situation, Professor Smith observed that "ethnically similar and/or geographically close city-states allied to form regional political confederations."

By 1300, eight confederations of various sizes occupied the entire Valley of the México and adjacent areas.

As the late arrivals in the Valley of México, the Mexica were hard-pressed to find a home, which they could call their own. In A.D. 1325, once again on the run, the Mexica wandered through the wilderness of swamps that surrounded the salty lakes of the Valley of México.

On a small island, the Mexica finally found their promised omen when they saw a cactus growing out of a rock with an eagle perched atop the cactus. The Mexica high priests thereupon proclaimed that they had reached their promised land. As it turns out, the site turned out to be a strategic location, with abundant food supplies and waterways for transportation.

The Mexica settled down to found their new home, Tenochtitlán (Place of the Cactus Fruit). The Mexica became highly efficient in their ability to develop a system of dikes and canals to control the water levels and salinity of the lakes. Using canoes and boats, they were able to carry on commerce with other cities along the valley lakes. And, comments Professor Smith, "the limited access to the city provided protection against military attack."

Huitzilihuitl, who ruled the Mexica from 1391 to 1415, writes Professor Smith, "presided over one of the most important periods in Mexica history; The Mexica became highly skilled as soldiers and diplomats in their dealing with neighbors. One of Huitzilihuitl's major accomplishments was the establishment of successful marriage alliances with a number of powerful dynasties." Over time, the Mexica, as the latecomers and underdogs of the Valley region, sought to increase their political power and prestige through intermarriage.

"Marriage alliances," writes Professor Smith, "were an important component of diplomacy among Mesoamerican states. Lower ranking kings would endeavor to marry the daughters of more powerful and important kings. A marriage established at least an informal alliance between the polities and was a public acknowledgement of the dominant status of the more powerful king."

Sometime around 1428, the Mexica monarch, Itzcoatl, ruling from Tenochtitlán, formed a triple alliance with the city-states of Texcoco and Tlacopan (now Tacuba) as a means of confronting the then-dominant Tepanecs of the city-state of Azcapotzalco. Soon after, the combined force of the Triple Alliance was able to defeat Azcapotzalco.

Later that year, Culhuacan and Huitzilopochco were defeated by the Alliance. A string of victories continued in quick succession, with the defeat of Xochimilco in 1429-30, Ixtapalapan in 1430, and Mixquic in 1432."

Professor Smith writes that "the three Triple Alliance states were originally conceived as equivalent powers, with the spoils of joint conquests to be divided evenly among them.

However, Tenochtitlán steadily grew in power at the expense of Texcoco and particularly Tlacopan." In time the conquests of the alliance began to take the shape of an empire, with the Triple Alliance levying tribute upon their subject towns. Professor Smith, quoting the words of the anthropologist Robert McCormick Adams, writes that "A defining activity of empires is that they are preoccupied with channeling resources from diverse subject polities and peoples to an ethnically defined ruling stratum."

With each conquest, the Aztec domain became more and more ethnically diverse, eventually controlling thirty-eight provinces. The Aztec tributary provinces, according to Professor Frances F. Berdan, were "scattered throughout central and southern México, in highly diverse environmental and cultural settings." Professor Berdan points out that "these provinces provided the imperial powers with a regular and predictable flow of tribute goods."

Of utmost importance became the tribute that made its way back to Tenochtitlán from the various city-states and provinces. Such tribute may have taken many forms, including textiles, warriors' costumes, foodstuffs, maize, beans, chilies, cacao, bee honey, salt and human beings (for sacrificial rituals). Aztec society was highly structured, based on agriculture, and guided by a religion that pervaded every aspect of life.

The Aztecs worshipped gods that represented natural forces that were vital to their agricultural economy.

For hundreds of years, human sacrifice is believed to have played an important role of many of the indigenous tribes inhabiting the Valley of México.

However, the Mexica brought human sacrifice to levels that had never been practiced before.

The Mexica Indians and their neighbors had developed a belief that it was necessary to constantly appease the gods through human sacrifice.

By spilling the blood of human beings onto the ground, the high priests were, in a sense, paying their debt to the gods.

If the blood would flow, then the sun would rise each morning, the crops would grow, the gods would provide favorable weather for good crops, and life would continue.

Over time, the Mexica, in particular, developed a feeling that the needs of their gods were insatiable.

The period from 1446 to 1453 was a period of devastating natural disasters: locusts, drought, floods, early frosts, starvation, etc. The Mexica, during this period, resorted to massive human sacrifice in an attempt to remedy these problems. When abundant rain and a healthy crop followed in 1455, the Mexica believed that their efforts had been successful. In 1487, according to legend, Aztec priests sacrificed more than 80,000 prisoners of war at the dedication of the reconstructed temple of the sun god in Tenochtitlán.

By the beginning of the Sixteenth Century, the Aztec Empire had become a formidable power, its southern reaches extending into the present-day Mexican states of Oaxaca and Chiapas. The Mexica had also moved the boundaries of the Aztec Empire to a large stretch of the Gulf Coast on the eastern side of the continent.

But, as Professor Smith states, "rebellions were a common occurrence in the Aztec empire because of the indirect nature of imperial rule." The Aztecs had allowed local rulers to stay in place "as long as they cooperated with the Triple Alliance and paid their tribute."

When a provincial monarch decided to withhold tribute payments from the Triple Alliance, the Aztec forces would respond by dispatching an army to threaten that king.

Professor Smith wrote that the Aztec Empire "followed two deliberate strategies in planning and implementing their conquests." The first strategy was "economically motivated."

The Triple Alliance sought to "generate tribute payments and promote trade and marketing throughout the empire." Their second strategy deal with their frontier regions, in which they established client states and outposts along imperial borders to help contain their enemies."

In 1502, Moctezuma II Xocoyotl (the Younger) ascended to the throne of Tenochtitlán as the newly elected tlatoani. It was about this time when the Mexica of Tenochtitlán began to suffer various disasters.

While tribute peoples in several parts of the empire started to rebel against Aztecs, troubling omens took place, which led the Mexica to believe that their days were numbered. Seventeen years after Moctezuma's rise to power, the Aztec Empire would be faced with its greatest challenge and a huge coalition of indigenous and alien forces, which would bring an end to the Triple Alliance.

Indigenous Groups at Contact

The names of the ethnic groups who traveled through or inhabited the Valley of México in the last 2,000 years include the Olmeca, Xicalanca, Tolteca, Chichimeca, Teochichimeca, Otomí, Culhuaque, Cuitlahuaca, Mixquica, Xochimilca, Chalca, Tepaneca, Acolhuaque, and Mexica.

The Otomí.

It is believed that the Otomí may have been the earliest inhabitants of the Valley of México. They were the only major indigenous group in the Valley of México who spoke a language other than Náhuatl. They had probably arrived in the Valley from the west after the destruction of Tula. Xaltocan, in the northern part of the Valley, was the capital of Otomí Empire during its prime in the mid-Thirteenth Century. However, the Otomí declined in power and prestige during the Fourteenth Century, after having lost wars with the Mexica.

Culhuaque.

The Culuaque Indians inhabited Culhuacan near the tip of the peninsula that separated Lake México from Lake Xochimilco. The Culhuaque Indians settled in Culhuacan sometime around the Twelfth Century and were the original masters of the Mexica before the establishment of Tenochtitlán. In the mid Fourteenth Century, the Mexica defeated the Culhuaque, partly as a result of Tepaneca expansion from Azcapotzalco. Culhuacan was later conquered in 1428 by the Mexica.

Cuitlahuaca.

The Cuitlahuaca occupied an insular community called Cuitlahuac (Tlahuac), which was located between Lakes Chalco and Xochimilco). The Cuitlahuaca were surrounded by the Xochimilca, Mixquica, and Chalca to the south, and the Culhuaque, Mexica, and Acolhuaque to the north. They were conquered by the Mexica in the Fifteenth Century.

Xochimilca.

The Xochimilca migrated to the southern part of the Valley of México and gave their name - meaning "Plantation of Flowers" - to their primary settlement. Although they conquered some of their neighbors, eventually they declined after fighting wars with Huejotzingo, Tlaxcala, and Cholula on their eastern frontier.

The Colonial Period

For three full centuries (1521-1821), México City and the surrounding jurisdiction underwent a period of integration, assimilation, and Hispanization. This period - which is not the focus of this work - has been discussed in many books. One particularly informative source about the cultural and social development of central México is James Lockhart's The Náhuas After the Conquest: A Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central México, Sixteenth Through Eighteenth Centuries (published in 1992 by the Stanford University Press). Another useful source to consult on this topic would be Charles Gibson's The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of México 1519-1810 (published by the Stanford University Press in 1964).

Although Spanish became the primary language of this region, many aspects of indigenous culture and language remained. When the population of the jurisdiction of México was tallied in 1790, 742,186 persons were registered as "indios," representing 71.1% of the total population of 1,043,223.

In contrast, people of Spanish origin were tallied at 134,965.

The Federal District in the Twentieth Century

In the following chart, the reader will see the population of the Federal District from the time of the 1930 census to the 2000 census. I have provided comparable statistics for the Mexican Republic for the same years.

THE FEDERAL DISTRICT - INDIGENOUS POPULATION STATISTICS (1930-2000)

| Year | D.F. - Speakers of Indigenous Languages Aged 5 Years and Over | D.F. - Total Population Aged 5 Years and Over | % Of Population Speaking Indigenous Languages | Mexican Republic - Speakers of Indigenous Languages | Mexican Republic - Total Population |

| 1930 | 14,676 | 1,076,276 | 1.36% | 2,251,086 | 14,028,575 |

| 1950 | 18,812 | 3,050,442 | 0.62% | 2,447,609 | 25,791,017 |

| 1990 | 111,552 | 7,373,239 | 1.51% | 5,282,347 | 70,562,202 |

| 2000 | 141,710 | 7,738,307 | 1.83% | 6,044,547 | 84,794,454 |

|

Notes: The census data refers to the following census dates: May 15

(1930), June 6 (1950), March 12 (1990), February 14 (2000). Note: Census

data for indigenous language speakers refers to persons who speak only

indigenous languages and those who speak both one indigenous language

and Spanish. Source of 1930 data: Secretaria de la Economia Nacional, Annuario Estadistico de Los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1941 (México, 1943) Source of 1950 data: Secretaria de la Economia Nacional, Annuario estadistico de Los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 1951-1952 (México, 1943). Source of 1990 data: INEGI, Estados Unidos Mexicanos. XI Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 1990, Resumen General. Source of 2000 data: INEGI, Estados Unidos Mexicanos. XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 2000, Tabulados Básicos y por Entidad Federativa. Bases de Datos y Tabulados de la Muestra Censal. |

| Copyright © 2003, John P. Schmal. All Rights Reserved |

In the unique 1921 Mexican census, residents of each state were asked to classify themselves in several categories, including "indígena pura" (pure indigenous), "indígena mezclada con blanca" (indigenous mixed with white) and "blanca" (white). Out of a total district population of 906,063 people, 169,820 individuals (or 18.7%) claimed to be of pure indigenous background. A much larger number - 496,359, or 54.8% - classified themselves as being mixed, while 206,514 individuals (22.8%) classified themselves as white.

The significance of this census data indicates that while many of the descendants of the Mexica and other indigenous groups in the Federal District may have not spoken their ancestral tongue, they did indeed profess to be of indigenous background and culture.

Five decades later, in the 1970 census, we witness a significant increase in the indigenous speaking population five years of age or more to 68,660 individuals. The largest language groups spoken out of this tally were: the Náhuatl (15,039 persons), Otomí (14,714), Zapoteco (14,109), Mixteco (7,513), Maya (4,341), Mazahua (4,286), and Purépecha (2,148). Already, the migrant population from the south brought forth significant numbers of Mixtecs and Zapotecs from Oaxaca and Maya from Chiapas and Yucatán.

According to the 2000 census, the population of persons five years and more who spoke indigenous languages in the Federal District amounted to 141,710 individuals. These individuals spoke a wide range of languages, many of which are transplants from other parts of the Mexican Republic.

The largest indigenous groups represented in the District were: Náhuatl (37,450), Otomí (17,083), Mixteco (15,968), Zapoteco (14,117), Mazahua (9,631), Mazateco (8,591), and Totonaca (4,782).

With 141,710 indigenous speaking individuals aged five and over living within its boundaries during the 2000 census, the Federal District boasts a large density of Indians. However, the percentages of Indians in individual delegaciones are actually quite small.

The southeastern delegación, Milipa Alta - with 3,862 indigenous speakers - has the largest percentage with 4.53%. However, Iztapalapa - with an indigenous population of 32,141 - has the largest absolute number of indigenous speakers, but a smaller percentage (2.04%). Gustavo A. Madero Delegación - in the northeastern sector of the District - has the second largest number of indigenous speakers with 17,023 (1.52%).

The Zapotecs and Mixtecs appear to be evenly distributed through the various delegaciones. Their significant presence in the Federal District is an obvious testament to the migrant nature of the Distrito Federal's population, where 1,827,644 persons - or 21.24% - stated that they were born in another political entity. Of this total, however, natives of Oaxaca - numbering 183,285 - represented 10.03% of the total migrant population. Only the states of México and Puebla have contributed larger numbers of migrants to the District.

Estado de México in the Twentieth Century

The state of México has retained a great number of indigenous speaking peoples. In spite of the effects of assimilation and migration, a significant portion of the state population identify with their Indian cultural and linguistic roots.

In the 1921 Mexican census, the state of México boasted a population of 884,617, of which 372,703 persons claimed to be of pure indigenous background, representing 42.1% of the total. An even larger number - 422,001, or 47.7% - classified themselves as being mixed, while only 88,660 (10%) considered themselves to be white.

According to the 2000 census, the population of persons five years and more who spoke indigenous languages in the state of México totaled 361,972 individuals. A large range of languages is spoken in the state of México, many of them imported from southern or eastern Mexican states. The most common indigenous languages spoken is the Mazahua tongue, with a total of 113,424 indigenous speakers, representing 31.3% of all the indigenous speakers five years of age and over in the state.

The second most common language is the Otomí, spoken by 104,357 indigenous speakers, and representing 28.8% of the total indigenous speaking population. The most common languages spoken are:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 1990, a total of 450,000 indigenous language speakers lived in a place other than their place of birth, representing 8.7 percent of the national total. Within this global migratory stream, the most outstanding is the State of Oaxaca with migrants totaling nearly one third of the total (142,000), and Yucatan with slightly over one sixth of the total (82,000). Seen from the perspective of the poles of attraction, the Federal District was the primary destination of migrants (93,000), followed by the State of México (9,000) and Quintana Roo (78,000).

Below, I have illustrated the municipios, which contain the largest percentages of indigenous speaking persons five years of age or more:

| MÉXICO - MUNICIPIOS WITH AT LEAST TEN PERCENT POPULATIONS OF INDIGENOUS SPEAKERS (All Statistics based on Persons Aged 5 Years or More) |

| No. |

| Municipio |

| % Indigenous Population |

| Population |

| Primary Language Group |

| 01 | Temoaya | 35.65 | 20,488 | Otomí |

| 02 | San Felipe del Progreso | 28.20 | 40,773 | Mazahua |

| 03 | Temascalcingo | 26.35 | 13,097 | Mazahua |

| 04 | Morelos | 24.26 | 5,044 | Otomí |

| 05 | Donato Guerra | 24.23 | 5,497 | Mazahua |

| 06 | Ixtlahuaca | 20.37 | 19,799 | Mazahua |

| 07 | Atlacomulco | 17.78 | 11,109 | Mazahua |

| 08 | Acambay | 16.84 | 7,756 | Otomí |

| 09 | Chapa de Mota | 15.68 | 2,961 | Otomí |

| 10 | El Oro | 15.48 | 3,754 | Mazahua |

| 11 | Jiquipilco | 13.42 | 6,159 | Otomí |

| 12 | Otzolotepec | 10.06 | 4,852 | Otomí |

| Copyright © 2003, John P. Schmal. All Rights Reserved |

The Mazahua Indians - representing the most populous indigenous-speaking group in México - primarily occupy thirteen municipios in the northwestern portion of the state of México. Mazahuas also inhabit some municipios in the center of the state, as well as parts of eastern Michoacán. They are a division of the Oto-Manguean linguistic group and are related by both culture and language to the Otomí, from whom they are descended.

The Mazahua are believed to have been among the original tribes who migrated to central México during the Thirteenth Century. In 1521, Hernán Cortés - after subduing the Mexica - consolidated his power by sending Gonzalo de Sandoval to subdue all resistance among the Aztec neighbors: the Mazahuas, Matlazincas and Otomies. Very quickly, Gonzalo de Sandoval brought the Mazahua Indians under Spanish control, and the Franciscan missionaries played a prominent role in bringing Christianity to their people.

Today, most of the Mazahua are engaged in agricultural pursuits, specifically the growing of maize, pumpkin, maguey and frijol. In the years since the Conquest, the Mazahua population has evolved and its cultural elements, social organization, and religion have developed into a hybrid culture drawing from several cultural elements. No one is certain about the origin of the word Mazahua, but some have suggested that it is derived from the Náhuatl term, mázatl, meaning "deer."

The Mazahua make up a significant portion of the population of several municipios in the state. In the municipio of Atlacomulco, the population of Mazahua speakers five years of age and over in 2000 consisted of 10,709 individuals, making up 17.1% of the population of the municipio. In the municipio of Donato Guerra, 5,419 Mazahuas represented 24% of the population of the municipio. In Ixtlahuaca, 19,203 Mazahuas represented 19.8% of the total population.

The Otomí are the second largest linguistic group in México state. They call themselves "Hñahñu," the word Otomí having been given to them by the Spanish. Otomí are a very diverse indigenous group, living in many communities throughout Central México and speaking a great variety of dialects, some of which are not mutually intelligible. Like the Mazahuas, they belong to the Oto-Manguean linguistic group. Significant numbers of Otomies occupy 14 of the 121 municipios in the state of México, most of these municipios being located in the northwest (Atlacomulco-Timilpan) and in the center (Toluca-Lerma).

Although the Náhuatl-speaking population is the most populous group in the entire Mexican Republic, they are ranked third place in the state of México, with more than 15% of the total indigenous-speaking population.

The influence of migrant labor is particularly significant to the state of Mexico. Out a total population of 13,096,686 in the 2000 census, 5,059,089 individuals - or 38.6% - were born in another political entity than the state of México. The primary states contributing to México's migrant population were - in numerical order - the Federal District (more than 3 million people), Puebla (295,889 migrants), Oaxaca (256,786), Hidalgo (256,718), and Michoacán (231,811). Oaxaca's significant contribution amounted to 5.1% of the migrant pool, which explains why the Mixteco and Zapoteco languages from Oaxaca are the fourth and fifth most common indigenous groups in the state.

The Mazateco speakers represented the sixth largest group in 2000. Speakers of this language are mainly migrants from the states of Oaxaca and Guerrero. They are also classified as a division of the Oto-Manguean linguistic group. The Totonaca speakers - numbering more than 8,000 individuals in 2000 - are descendants of Cortés' coastal allies in Veracruz and it is likely that many of these people are from the eastern seaboard area. The Mixe, Chinanteco, and Tlapaneco peoples are primarily found in Guerrero and Oaxaca.

Nearly five hundred years after the conquest and destruction of the Aztec Empire, the culture, language and spirit of the Náhuatl, Otomí, Mazahua and other indigenous peoples remains intact within the central Hispanic culture to which most of them also belong. It is worth noting that, although the Mexica capital Tenochtitlán was occupied after an eighty-day siege, many of the indigenous peoples of Central México quietly submitted to Spanish tutelage. In this way, they were given an opportunity to retain some elements of their original culture, while becoming an integral and important part of a new society.

TIES TO THE PAST, THE BLOODLINE REMAINS UNUSUALLY PURE

In the most comprehensive genetic study of the Mexican population to date, researchers from UC San Francisco and Stanford University, along with Mexico’s National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), have identified tremendous genetic diversity, reflecting thousands of years of separation among local populations and shedding light on a range of confounding aspects of Latino health.

The study, which documented nearly 1 million genetic variants among more than 1,000 individuals, unveiled genetic differences as extensive as the variations between some Europeans and Asians, indicating populations that have been isolated for hundreds to thousands of years.

These differences offer an explanation for the wide variety of health factors among Latinos of Mexican descent, including differing rates of breast cancer and asthma, as well as therapeutic response. Results of the study, on which UCSF and Stanford shared both first and senior authors, appear in the June 13 online edition of the journal Science.

“Over thousands of years, there’s been a tremendous language and cultural diversity across Mexico, with large empires like the Aztec and Maya, as well as small, isolated populations,” said Christopher Gignoux, PhD, who was first author on the study with Andres Moreno-Estrada, MD, PhD, first as a graduate student at UCSF and now as a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford. “Not only were we able to measure this diversity across the country, but we identified tremendous genetic diversity, with real disease implications based on where, precisely, your ancestors are from in Mexico.”

For decades, physicians have based a range of diagnoses on patients’ stated or perceived ethnic heritage, including baseline measurements for lung capacity, which are used to assess whether a patients’ lungs are damaged by disease or environmental factors. In that context, categories such as Latino or African-American, both of which reflect people of diverse combinations of genetic ancestry, can be dangerously misleading and cause both misdiagnoses and incorrect treatment.

While there have been numerous disease/gene studies since the Human Genome Project, they have primarily focused on European and European-American populations, the researchers said. As a result, there is very little knowledge of the genetic basis for health differences among diverse populations.

“In lung disease such as asthma or emphysema, we know that it matters what ancestry you have at specific locations on your genes,” said Esteban González Burchard, MD, MPH, professor of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences, and of Medicine, in the UCSF schools of Pharmacy and Medicine.

Burchard is co-senior author of the paper with Carlos Bustamante, PhD, a professor of genetics at Stanford. “In this study, we realized that for disease classification, it also matters what type of Native American ancestry you have.

In terms of genetics, it’s the difference between a neighborhood and a precise street address.”

Three Distinct Genetic Clusters in Mexico

The researchers focused on Mexico as one of the largest sources of pre-Columbian diversity, with a long history of complex civilizations that have had varying contributions to the present-day population. Working collaboratively across the institutions, the team enlisted 40 experts, ranging from bilingual anthropologists to statistical geneticists, computational biologists and clinicians, as well as researchers from multiple institutions in Mexico and others in England, France, Puerto Rico and Spain.

The study covered most geographic regions in Mexico and represented 511 people from 20 indigenous and 11 mestizo (ethnically mixed) populations. Their information was compared to genetic and lung-measurement data from two previous studies, including roughly 250 Mexican and Mexican-American children in the Genetics of Asthma in Latino Americans (GALA) study, the largest genetic study of Latino children in the United States, which Burchard leads.

Among the results was the discovery of three distinct genetic clusters in different areas of Mexico, as well as clear remnants of ancient empires that cross seemingly remote geographical zones. In particular, the Seri people along the northern mainland coast of the Gulf of California and a Mayan people known as the Lacandon, near the Guatemalan border, are as genetically different from one another as Europeans are from Chinese.

"We were surprised by the fact that this composition was also reflected in people with mixed ancestries from cosmopolitan areas,” said co-first author Moreno-Estrada, a life sciences research associate at Stanford. "Hidden among the European and African ancestry blocks, the indigenous genetic map resembles a geographic map of Mexico.”

A representative chart of a diverse genome, reflecting varied heritage across one individual’s genes, can be found on the Burchard Lab website.

The study was supported by the Federal Government of Mexico, Mexican Health Foundation, Gonzalo Rio Arronte Foundation, George Rosenkranz Prize for Health Care Research in Developing Countries, UCSF Chancellor’s Research Fellowship, Stanford Department of Genetics, National Institutes of Health (grants GM007175, 5R01GM090087, 2R01HG003229, ES015794, GM007546, GM061390, HL004464, HL078885, HL088133, RR000083, P60MD006902 and ZIA ES49019), National Science Foundation, a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Amos Medical Faculty Development Award, Sandler Foundation, America Asthma Foundation and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

UCSF is the nation’s leading university exclusively focused on health. Now celebrating the 150th anniversary of its founding as a medical college, UCSF is dedicated to transforming health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. It includes top-ranked graduate schools of dentistry, medicine, nursing and pharmacy; a graduate division with world-renowned programs in the biological sciences, a preeminent biomedical research enterprise and two top-tier hospitals, UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital San Francisco.

A SOURCE FOR FINDING TIES TO INDIGENOUS TRIBES IN MEXICO

Many people may not know that FamilySearch, an international nonprofit organization headquartered in Salt Lake City, Utah, and online at FamilySearch.org, has amassed over 100 million historical records from Mexico. And FamilySearch continues to add more records each year.

Arturo Cuéllar-Gonzalez, a research specialist for Latin America at FamilySearch’s Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, has made it his full-time passion and vocation to help patrons discover their Latin roots. His interest in family history began in 1986, when his grandmother “planted in my heart the deep desire to find my ancestors.”

Cuellar spends his days helping patrons in the Family History Library. He is an accredited genealogist and has researched his personal family history records back 11 generations.

In the last couple of years, Cuellar has observed more young people getting interested in family history. He said, “They often tell me it gives them a nice feeling inside.” Many of them are becoming more aware of their family’s history because of Facebook posts from family and relatives.

For the millions of people with Mexican ancestry who want to celebrate by learning more about their Mexican heritage, he recommends six quick research tips.

1. The 1930 Mexico Census

Prior to the Mexican Revolution, 95 percent of the land in Mexico was owned by 5 percent of the people. In preparation to form a policy of land distribution, the Mexican government created a census so land ownership could be recorded and conveyed. This was one of the first mandatory accountings of everyone and included name, age, gender, birthplace, address, marital status, nationality, religion, occupation, real estate holdings, literacy, any physical or mental defects, and any Indian language spoken. The 1930 Mexico census can be searched freely online at FamilySearch.org.

2. Mexican Civil Registration Records

Mexico’s civil registration records (births, marriages, and deaths) were the first records kept by local governments. They were started in 1857 under the direction of Benito Juarez, a reformer who separated the church from the government. Before then, the only records kept were in the various churches. The churches resisted releasing their records, but changing the schools from parochial to public schools required family records. You can find many of Mexico’s civil registration records online at FamilySearch.org.

3. Parish Records

Catholic parish records began in 16th century when Spain took over the country. They installed the government and the Catholic Church in every city. Parish records show christening, baptism, and marriage records, including marriage information files. Those marriage information files came from interviews by priests who needed to prove that the bride and groom were not related or from another place and that the groom was not trying to become a priest. Some of those records include several pages of information, a gold mine for family history researchers, showing generations of ancestry to prove that the bride and groom were faithful Catholics.

4. Family Clues

Finding where your ancestors were from using family clues is the fourth research tool. That process is as much an art as science. The types of food your ancestors ate, family recipes, songs, and stories handed down for generations are hints that may give you some guidance. The type of climate or terrain or major storms and destruction you’ve heard shared through family stories can provide other clues. Old pictures in unique settings or with writing on them or the types of dress shown in the photos might help. Once the place is found, parish records may supply the needed information.

5. Notarial Records

Notarial records include records from the sale of property or making a will. These records date back to the 1650s, and not many are filmed, but they can be found in local archives. FamilySearch staff might also be able to assist in writing correspondence to custodians of notarial records in Mexico.

6. The FamilySearch.org Wiki

The FamilySearch.org wiki is a rich resource for family history researchers. It has nearly 3,000 articles written by Mexico research specialists to help you navigate the available resources and give you additional insightful information. For example, Mexican surnames are not always helpful because during a revolution some people changed their names. Or you can enter a location in the search field and see what resources exist for that locality.

While you are gathering with family and friends to celebrate Cinco de Mayo or your Mexican family heritage, do some sleuthing. Pay more attention to those old family recipes, stories, documents, and photos, and look for the telltale clues that give you key insights and appreciation for those who have gone before you. Preserve and explore these resources together at FamilySearch.org so that next year in your celebrations you will have an even deeper appreciation."

A FEW INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT OAXACA:

Prominent natives of Oaxaca include Benito Juárez, Porfirio Díaz, José Vasconcelos (a writer who greatly influenced the Mexican Revolution), famed painters Rufino Tamayo and Francisco Toledo and baseball hero Vinicio (Vinny) Castilla.

Benito Juarez, arguably Mexico’s most famous president, was Zapotec. It has been the only Mexican president with indigenous ascent.

El Árbol del Tule, a Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum), or ahuehuete (meaning "old man of the water" in Nahuatl) has the stoutest trunk of any tree in the world. In 2001 it was placed on a UNESCO tentative list of World Heritage Sites.

The age is unknown, with estimates ranging between 1,200 and 3,000 years, and even one claim of 6,000 years; the best scientific estimate based on growth rates is 1,433-1,600 years.

Local Zapotec legend holds that it was planted about 1,400 years ago by Pecocha, a priest of Ehecatl, the Aztec wind god, in broad agreement with the scientific estimate; its location on a sacred site (later taken over by the Roman Catholic Church) would also support this.

In 1990, it was reported that the tree is slowly dying because its roots have been damaged by water shortages, pollution, and traffic, with 8,000 cars travelling daily on a nearby highway.

Each year the indigenous cultures of the state are celebrated in an event called La Guelaguetza. Groups from the 8 regions come together to celebrate in an event believed to have pre Hispanic beginnings.

Oaxaca is home to a "petrified" waterfall, Hierve el Agua (shown below) ...made from mineral deposits in layer after layer over time.

DESPITE THE NATURAL BEAUTY AND ARCHITECTURAL WONDERS OF OAXACA, IT IS A REGION WHOSE PEOPLE NEED HELP.

PERHAPS IF MORE PEOPLE NEW THE FACTS, HEARD FROM THE PEOPLE THEMSELVES WHAT IS HAPPENING THERE, SOMETHING WOULD BE DONE TO BRING THEM PEACE AND THE KILLINGS EVERY FEW YEARS WOULD CEASE.

ETHNIC CLEANSING ANYWHERE ON THIS GLOBE MUST NEVER BE TOLERATED, NO MATTER WHAT EXCUSE GOVERNMENTS GIVE FOR IT.

___________________________

FURTHER READING:

~Life after the Massacre: A View from Oaxaca

http://nacla.org/news/2016/06/28/life-after-massacre-view-oaxaca

http://nacla.org/news/2016/06/28/life-after-massacre-view-oaxaca

~Rufino Tamayo famous paintings

Sources:

John Schmal and Donna Morales, "Mexican-American Genealogical Research: Following the Paper Trail to Mexico" (Heritage Books, 2002)

Campillo Cuautli, Héctor. Distrito Federal: Monografía Histórica y Geográfica. México: D.F.: Fernández Editores, 1992.

Davies, Nigel. The Aztecs: A History. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma, 1980.

Departamento de la Estadística Nacional, Annuario de 1930. Tacubaya, D.F., México, 1932.

Hassig, Ron. Aztec Warfare: Imperial Expansion and Political Control. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Hodge, Mary G. "Political Organization of the Central Provinces," in Frances F. Berdan et al., Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996, pp. 17-45.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). Estados Unidos Mexicanos. XII Censo General de Población y Vivienda, 2000. Tabulados Básicos y por Entidad Federativa. Bases de Datos y Tabulados de la Muestra Censal.

Jiménez, Carlos M. The Mexican American Heritage. Berkeley, California: TQS Publications, 1994 (2nd edition).

Marks, Richard Lee. Cortés: The Great Adventurer and the Fate of Aztec México. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

Meier, Matt S. and Feliciano Rivera. The Chicanos: A History of Mexican Americans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1972.

Meier, Matt S. and Feliciano Ribera. Mexican Americans, American Mexicans: From Conquistadors to Chicanos. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993.

Meyer, Michael C. and Sherman, William L. The Course of Mexican History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Secretaria de la Economia Nacional, Compendio Estadistico. México, D.F., 1947.

Smith, Michael E. "The Strategic Provinces," in Frances F. Berdan et al., Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1996, pp. 137-150.

Smith, Michael E. The Aztecs. Cambridge, Mass.: Blackwell Publishers, Inc., 1996.

Spitler, Susan. "Homelands: Aztlan and Aztlán," Online: http://www.tulane.edu/~anthro/other/humos/sample.htm. November 20, 2001.

No comments:

Post a Comment